Cloud cover is creeping polewards shifting storms and widening deserts

Bands cloud cover that swirl around the globe are slowly creeping towards the poles, causing dry regions to expand around the equator, climate scientists have warned. Using satellite data captured between the 1980s and 2000s, researchers found that channels of cloud cover which carry storms around the globe have shifted closer to the poles over time. As well as poleward shift in cover and expanding dry regions, they findings show the height of cloud tops have increased at all latitudes, all of which impacts on the global climate and agree with predictions for the impact of climate change.

Cloud cover is a key factor in regulating the planet's temperature, with cover reflecting solar radiation back into space or acting as a blanket to keep surface heat from escaping, depending on the type and thickness of clouds. But while the effects of such a variable system are almost impossible to decipher in the short term, over a period of decades long-term trends begin to emerge.

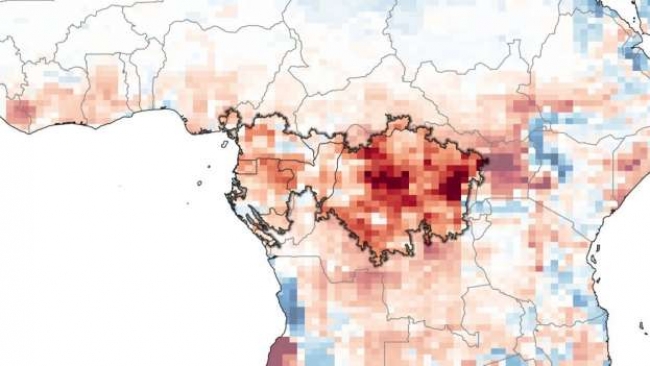

Led by climate scientists at the University of California, the team was able to correct the satellite data from several sources to show such long term trends, removing errors and inaccuracies from satellite sensors and erroneous trends. They found that dry bands over the subtropical regions are expanded – a belt which covers regions including the Southern United States, North Africa and Central Australia – and the height of cloud tops at all latitudes has increased.

They say the findings agree with climate models, which predict a warming climate will be accompanied with less cloud coverage in the tropics and growing dry regions. 'What this paper brings to the table is the first credible demonstration that the cloud changes we expect from climate models and theory are currently happening,' said Professor Joel Norris, a climate scientist at the Scripps Institute for Oceanography in California, who led the research.

According to the researchers, the effect on cloud cover has been caused by a combination of greenhouse gases from human activity over several decades. But compounding this warming effect is the bounce back from two large volcanic eruptions – the El Chichón eruption in Mexico in 1982 and the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines – which had a far reaching cooling effect on the climate. When combined, these two factors result in a positive feedback loop, warming the climate.

They researchers add that the trend is set to continue in future with the release of more greenhouse gases, unless there is substantial volcanic activity to offset the warming effect from shifting cloud cover.

Source: Daily Mail

Tue 12 Jul 2016 at 07:35

.jpg)